December 14, 2015

A December Fed rate hike could be messy: QE conditions could spring a bond market surprise

Commentary by Robert Balan, Chief Market Strategist

"We want to make sure that, having achieved this progress in the labor market, we maintain it and don’t put it in danger (with rapid policy rate increases).”

Janet Yellen, Chair, Federal Reserve Bank, December 9, 2015

Even before the US Federal Reserve Bank meets on December 15 and 16, most investors have already concluded that the central bank will raise policy rates for the first time since 2006. A rate hike in December of course affirms to investors and symbolizes that the preconditions the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) set for raising interest rates have been met. A rate hike is therefore symbolic in the following sense: (1) the Fed has confidence that the soundness of the banking and financial system will not be impaired by the withdrawal of bank reserves, (2) the FOMC is convinced that the toolset used to manage reserves in the banking system has sufficient flexibility to stabilize the policy rate within the range desired by the FOMC, (3) that the slack in labor market has been removed, with the official Unemployment rate close to full-employment levels and hourly wages rising past 2.0% annualized rate, (4) the FOMC believes US core inflation will rise to a 2% annualized rate, (5) that increases in US policy rates will not cause or exacerbate economic stresses in the US, and especially in EM economies, and finally, (6) that higher policy rates will not cause the US dollar to appreciate significantly further against both developed and EM currencies. Therefore, it follows that a policy rate increase that upends one or several of these preconditions jeopardizes the Fed's credibility and, by implication, the central banks' ability to stabilize the policy rate at desired levels and secure investors' confidence. The preconditions are too numerous in our opinion, and some of the objectives are in conflict, and even mutually exclusive. We fear that the aftermath of a Fed rate hike in December will be messy. The longest and most radical monetary-easing cycle in the history of the U.S. has created a mind-boggling stash of cash in the banking system. Commercial banks hold $2.5 trillion in excess reserves – money they essentially have parked at the Federal Reserve that has remained inert for several years now. And the Fed itself has $4.48 trillion in its balance sheet.

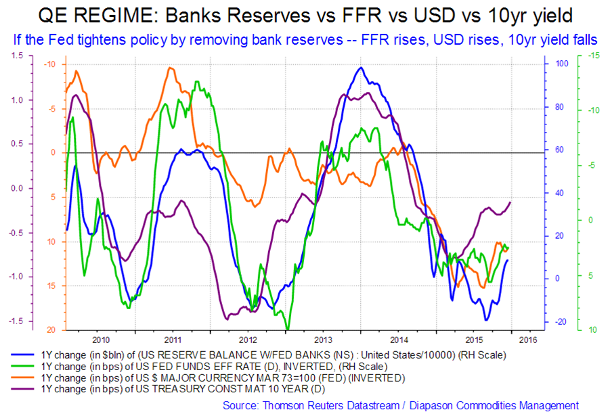

So many investors are on edge, and rightly so. The problem has transcended the usual debate on the propriety of a policy raise now; there is a logistical concern as well. With so much cash stashed inside the system, will the Fed be able to nudge rates to the level that they want? Will the new-fangled toolset they’ve created to implement the policy change do the work, or will it sow confusion instead – the kind of crisis of confidence that can damage the Fed’s credibility and trigger a broad inter-market selloff? We believe that the likelihood of a messy aftermath of a Fed rate hike in December is not trivial at all. And the reason is that plenty of investors have not understood the changes in the relationships and behavior of asset classes brought about by quantitative easing. Let us look at some examples. A bond market rout last week that saw two-year yields rise to a five-year high. There is nothing wrong with that, one may suppose, because tightening the policy rate makes interest rates go higher – that has always been the historic response of bond yields to policy tightening in the past. But what if bond yields FALL instead of RISE in the aftermath of a Fed hike in December? Our work shows that what used to be the norm before the Great Financial Crisis – before the days of the TALFs, TARPs and QEs – does not necessarily apply after the accumulation of so much reserves in the system. For instance, tightening policy in the QE environment via diminution of reserves may cause bond yields to FALL rather than RISE. The empirics of this claim can easily be shown, as in the case of the chart below.

A bond market rout last week saw the 2-yr and 10yr US Treasury yields rise to five-year highs. We would expect more of the same from the Treasury market leading to what is almost a given by now – a policy rate hike on December 16. But there are pitfalls down the road for this higher-yield strategy. There are still issues with the Fed’s humongous balance sheet. The Fed will be deploying new methods to drain that liquidity and push rates higher in the interbank lending market, which has become harder to influence now that cash-heavy banks rely on it infrequently. Some strategists say that policy makers will need to more than triple the size of its current daily reverse-repo program (RRP) to at least $1 trillion. But the Fed may balk at the move because officials have signalled their wariness of playing too big a role in money markets. The RRP program brings another wrinkle: the Fed will tap an expanded pool of counterparties, including investment companies. It used to just deal with primary dealers, a group that currently numbers 22. With so may moving parts, a rate hike in December runs the risk of missteps, from either the investors, the Fed, or from both. In such an event, investors would naturally fly into the safety of Treasuries. We therefore believe that the likeliest outcome will be a sharp decline in bond yields following a rate hike in December.

|

Main drivers this week:

|

Commodities and Economic Highlights

Commentary by Sammer Khatlan, Oil Analyst

Diamonds aren’t forever: future metals supplies at risk as miners feel the squeeze

The global commodities rout continues to tally victims as shares in oil, mining and any other resource-related companies take a huge hit. It is a hard time across the commodity complex whether you are an investor, employee or owner, in what has effectively been the worst commodity collapse in a generation. As we enter a period of severe distress, some companies are unlikely to survive the ruthless pricing environment: according to Standard & Poor’s, financial trouble for commodity companies has already increased global corporate defaults to the highest level since 2009 as credit metrics for metals and miners deteriorate dramatically.

Anglo American, BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto and Glencore have all seen their respective share values drop considerably this year. When in a hole, management usually has several options to strengthen balance sheets: sell assets, cut costs, reduce payouts or raise capital. Anglo American, the latest big name to raise the white flag, has announced a plan for the first three as declines in operating cash flow have aggressively outstripped cuts to capital investment. This has left no cash to pay for interest, dividends and taxes. Anglo’s debt hit $13.5bn in June, more than twice the cash flow from operations. Its new turnaround plans announced last week, will see dividend payments suspended for 18 months and two-thirds of its operations shed (this include 85,000 job cuts). Asset sales and closures will be outlined in February. Despite these restructuring plans, there is concern that Anglo has not been able to implement these turnarounds fast enough to stem the tide – to emphasise this point, the company has $5bn of loan debt and $15bn of bonds outstanding, nearly $11bn of which needs to be refinanced in the next five years. Unlike Glencore, who quickly raised $2.5bn from shareholders to help cut its borrowing, Anglo insists there is no need for fresh capital, implying its belief that the restructuring plan will suffice – it is unclear whether this is based on the expectation that prices will improve or that enough cash can be raised/recycled from asset sales, closures and cost cuts.

In our analysis of the oil sector, we have seen a worrying trend of capex and opex cuts, combined with project write-downs and delays that will see a huge hole in supply going forward. This trend is also playing out in the mining sector. The example of Anglo-American can illustrate this: finding buyers for negative cash flow assets will in itself be extremely difficult – however the pertinent issue is that these assets will not keep running until a deal is reached as this costs money that Anglo does not have. This is supply being cut off and future supply taken off the market. Considering the size of Anglo and that nearly 60% of assets will be trimmed implies a significant amount of output that will be out of commission. In the event of a successful asset sale, the process of winding down operations and then starting them up again, transferring or hiring a new workforce, maintenance or replacement of upstream/mining equipment is not a short one – there will be a sizeable lag in getting supply up and running. It is not just Anglo that will be halting production, miners across the market cap spectrum are struggling in the current price environment, meaning supply projects all over the world are at risk, if not already being taken offline with no new projects on hand to make up for this loss of supply. Potential buyers of assets may be scarce so it is likely that some mines may be indefinitely shutdown as they will only drain cash from the balance sheet – this will only further exacerbate the impending supply chasm.

Debt on the combined balance sheets of the ten biggest miners is more than 60% higher since 2008/09 when commodity prices and revenues last collapsed. Market cap value for these companies has roughly halved since a year earlier. Free cash flow has held up but only thanks to drastic cuts in capex. Further downside to commodity prices is likely in the short- to medium-term, which will continue to weigh on companies. This will result in better discipline on the supply side with cuts to marginal cost of production, but capex cuts and project write-offs/deferrals will significantly impact future supply growth. While sentiment at the front of the curve remains acutely negative, the seeds for the next mining boom are being sown as supply will fall out of sync with global demand growth (though likely at a slower pace this time). Rebalancing needs to continue, and from 2017 onwards substantial prices hikes are likely – this recovery will of course vary from commodity to commodity.

Venezuelan elections could spark unrest – oil industry will continue to suffer from neglect

The parliamentary elections held in Venezuela on December 6th were hugely significant yet largely overlooked by the oil markets. There has been virtually zero geopolitical risk premium on crude prices despite a myriad of global problems ranging from IS terrorising the Middle East, snail-like progress in Buhari’s new Nigeria and Yemen’s precarious ceasefire ahead of peace talks. Political risks have never been higher and developments in Venezuela are important.

United Democratic Roundtable (MUD) won 112 of the 167 seats in the National Assembly, giving the opposition a supermajority which grants them substantial powers to steer the country away from its “21st-century socialism”. This result marked the first time in 16 years that supporters of former president Chávez had lost its majority in the unicameral national assembly. The result also raises the possibility of a recall referendum on President Maduro in 2016 that could force him out; considering his military support and promises that he will not “surrender the revolution”, highlights the delicate and troubling political situation facing the nation in the coming months. The oil industry, already under severe stress, is at risk of further neglect and degradation as a consequence of this heightened political instability.

Crude accounts for 96% of Venezuela’s export revenues and the halving in prices over the last 18 months means that revenues have dropped to nearly $36bn compared to the average of the previous two years, just under $79bn. The dire situation of the nation’s finances cannot be downplayed: the central bank has already burned through $25bn in cash reserves; inflation is heading toward near unprecedented levels (reportedly 159% during this year alone); and the recession is expected to continue well-into 2016. Export revenues from oil will barely cover import needs, let alone pay back Venezuela’s debt and servicing its foreign bonds. During most of Chávez’s tenure, oil stood above $100/bbl: this paid (lavishly) for populist policies but also led to complacency and a failure to diversify. Maduro has similarly failed to implement any coherent economic policies. Reinvestment into exploration, production and refining has been non-existent and with the low price environment looking to persist in the medium-term, this will continue to hit the petro industry hard. A worrying trend has emerged as the economic crisis befalls the country. There has been a growing exodus of skilled oilfield workers from Venezuela, where real wages for technicians have fallen to the equivalent of under $400 a month, around 9% of the global average. The confluence of the world’s worst inflation, increasing crime rates and violence, and a plummeting currency, is prompting others to move abroad, dragging down crude output. The number of Venezuelans with active CVs on jobsites has surged – Rigzone.com numbers have jumped 22% this year through to October, up 68% versus 2011.

The oil infrastructure itself is fragile, especially those serving domestic use. Refinery throughput has suffered due to damage from fires and lack of investment to maintain the facilities. There has been a chronic shortage of replacement parts for rusted pumps and corroded pipelines, workers are repeatedly injured on-site and there have been frequent malfunctions and halting of operations. The Paraguana Peninsula, which contains the Amuay and Cardón refineries, has the potential to process nearly 1mmbd of oil, but production has been closer to 50% of capacity. Venezuela has resorted to joint-ventures with foreign companies and governments to sustain operations in its flagging oil industry, with September’s notable $5bn ‘special’ loan from China being the latest ‘boost’. Venezuela has garnered a lot of investment from foreign firms (especially those from China) but significant damage to the oil industry’s technical expertise, persistent underinvestment, and a poor climate for foreign investors, even if oil prices increase, means that it is unlikely that Venezuela’s crude industry will be able to rebound as readily as they did during the early 2000s.

Whilst claims that the opposition party will help the US regain control of Venezuela’s oil reserves are a little far-fetched (see PSUV’s Angel Rodriguez), the quote that “there will be confrontation” is a concern. Maduro’s acceptance of defeat after Dec 6th underlines the shifting dynamics in Caracas but he still controls the executive and judicial branches of government and more significantly, he still controls the military. The opposition, known for their deep divisions, were likely united in their hatred for Maduro and stuck to a non-violent path of resistance and ultimately victory. But the situation is precarious and violence can kick off between the parties, particularly if public unrest continues to intensify. The newly empowered opposition will have to tread carefully and lightly in order to keep the wounded hard-liners in the Chavista camp from lashing out and abusing the considerable power they still possess. There are constitutionally dubious tactics that Maduro can employ during the four-week lame-duck period ahead of the legislative change in January: for example, Maduro could pass a law to grant himself legislative powers and even disable the opposition-controlled chamber. One cannot doubt that the Chavistas will not retreat without a fight.

In the meantime, Venezuela’s oil infrastructure continues to degrade and deplete through a lack of any TLC. The mismanagement of the industry – zero investment, little maintenance and an ever-decreasing expertise base – and a series of unsuccessful nationalisations have sown the seeds of this oil-plight. The slow decline in the energy industry will take years to reverse and will require a credible resolution of the ongoing and future domestic political instability.

Chart of the week: Tightening policy in the QE environment may cause bond yields to fall

|

|