July 25, 2016

Austerity is on the way out, fiscal spending is in: Can the trough of interest rates be far behind?

Commentary by Robert Balan, Chief Market Strategist

"Fiscal stimulus calls for buying cyclicals, rather than looking at (stock) dividends and long duration bonds. The question is how much stimulus would be required to convince investors that it works.” Patrik Schowitz, global strategist at JPMorgan Asset Management

The main challenge facing the world economy is a shortfall in aggregate demand. This has been reflected in a surfeit of savings over investment, or equivalently, an excess of output over desired spending. The Great Financial Crisis (GFC) altered preferences in fundamental ways. For example, less than half of Americans told Gallup that they wanted to save more money before the financial crisis; today, that number has risen to two-thirds, according to the survey. And among households that want to spend more, stricter lending standards are preventing them from doing so. This is why up to this time, deflation, rather than inflation, has been the primary risk, as evidenced by the sharp drop in global bond yields to once unfathomable levels (negative in many parts of Europe, in fact). The origin of that shortfall in aggregate demand is clear. Before the Great Financial Crisis, cheap and abundant credit allowed poor households to spend more than they earned during the bubble years.

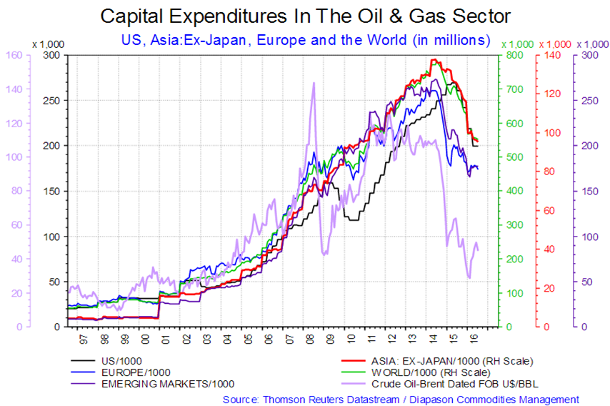

Meanwhile, corporations have been in no mood to increase capital spending. This is partly because heightened policy uncertainty has weighed on capex. It is also because the weak cyclical recovery in consumption in many countries has reduced the urgency to expand capacity. To makes matters worse, much of the softness in investment also reflects structural factors that will be difficult to overcome: (1) slower labor force growth has reduced the incentive for companies to build new factories and shopping malls, and (2) decreased household formation has also curbed the demand for new homes. (Please see the first fortnightly chart below).

Moreover, low commodity prices have reduced spending in the energy, mining, and materials sectors, which as recently as last year accounted for one-third of global capital expenditures among publicly-listed companies. The resource bust has, in turn, put tremendous pressure on emerging markets. That is unfortunate because EMs have been the main driver of rising investment spending for over a decade).

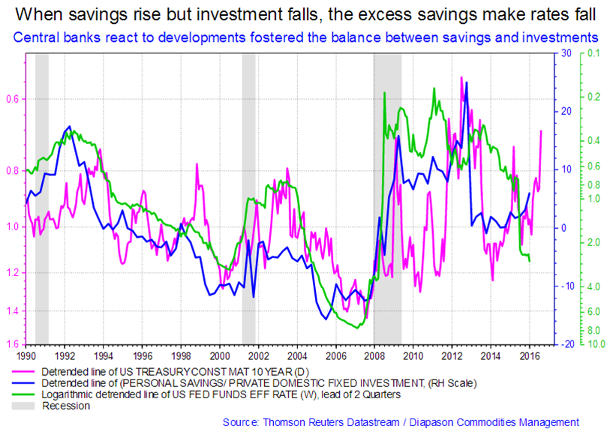

From the point of view of global aggregate demand, the world has been dealt a triple whammy. As a consequence, people and corporations have held back spending, for fear of another global growth slowdown, thereby launching a vicious cycle of the "Paradox of Thrift" – the desire of all households to save more can actually lead to a decline in aggregate savings. This had led to imbalances that are the root of today’s financial travails. Solid economic theory says that globally, savings must equal investment. This is not the product of some elaborate economic thought experiment, but a matter of simple arithmetic: income that is not consumed can be used to finance the production of new investment goods. When desired savings rise but desired investment declines, the excess savings make interest rates fall.

In a normal economy, lower rates discourage savings while encouraging firms to undertake marginally profitable investment projects – this is the self-correcting mechanism, which is often described as the “Business Cycle.” The problem, of course, is that nominal interest rates are already very low. And so the global economy continues to suffer from deflationary pressures, as all over the globe, people continue to save, depressing interest rates further.

Global central banks may determine short-term interest rates, but over longer horizons, interest rates are determined by the balance between spending and savings in the world as a whole – and central banks react to these developments when setting official short-term interest rates (Please see the second fortnightly chart below). Unfortunately, official policy rates across the globe are so low, in some cases in Europe even negative, so that there is only a limited scope for the credit channel to work.

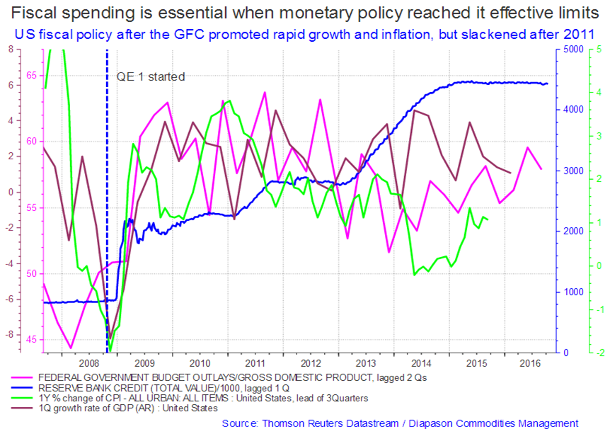

Given the conditions under which global central banks have to perform, and the fact that the usual policy tools that they have under disposal do not work very well under the current prevailing financial conditions, authorities have to come up with other policy tools that have not been used so far. Put another way, there is only so much that the central banks can do at this point. To break the economic logjam that the global economy is in right now, a new paradigm (fiscal spending), and another set of players (the global governments) have to enter the arena. (Please see third fortnightly chart below).

Politicians will start spending to protect their behind:

The Brexit vote was pivotal, and has reinforced our sense that the tide in the bond market is turning. Ironically, while global bond yields fell sharply in the wake of the polling results, the longer-term outcome is likely to be higher inflation and, ultimately, higher nominal yields. If policymakers around the world embrace reflationary policies in a bid to quell growing populism, inflation will rise; if they don’t, the resulting surge in anti-globalization sentiment will damage the supply side of the economy. The seeds of widespread global spending have been, or are being, sowed. It may take a while, but as seen from the US example after the Great Financial Crisis, with fiscal (deficit) spending, growth and inflation should follow.

We believe that policymakers will lean towards the former option, if only to protect their collective behinds. This is good news for risk assets. To be clear, calling for the end of the 35-year old global bond bull market is not the same as calling for a new bear market. The global economy continues to suffer from significant spare capacity, and this is likely to limit the ability of most central banks to engage in a full-blown tightening cycle. Globally, there is now $12tn of bonds yield less than zero, so many investors believe the limits of central banking have long been reached. This includes the Fed, which has a different dilemma – it runs the risk of pushing up the dollar again to punitive levels if it starts to raise rates too aggressively.

Nevertheless, with yields in most markets now below estimates of fair value, the natural inclination is to get a bit more bearish on bonds over the next quarters. The world is starting to embark on a new fiscal policy wave. In fact, fiscal policy was shifting in a more expansionary direction even before the Brexit vote. The Liberal government in Canada was elected partly on a promise to increase infrastructure spending. Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump have both pledged to boost government spending, with the latter also touting sizable tax cuts.

China had already began to loosen the fiscal screws. The Chinese may have no choice – official press in early May describing comments from an “authoritative person” that the government intended to dial back stimulus coincided with a slowing in credit growth and a deceleration in fiscal spending. But after growth and activity data deteriorated, the Chinese government reinstated the fiscal stimulus program and kicked-off a massive borrowing program. China, indeed, has to step up its stimulus program even further, if the government wants to set the economy up on an escape velocity trajectory.

Later in the year, the Japanese government is also set to ramp up fiscal stimulus (and possibly introduce what is looking suspiciously like helicopter-money policies) in a bid to push up inflation expectations. The Japanese government is likely to draw a supplementary budget this autumn that will feature new stimulus measures, including consumption vouchers for lower income workers. Even Germany has to eventually loosen in purse strings. It is natural to think that Germany will never accept helicopter money or any other policies that lead to higher inflation, based on past monetary policies. But what many do not realize is that it is actually in Germany’s interest to raise inflation. German corporate interests are dominated by banks and exporters -- groups that disproportionately benefit from easier monetary policies. Exporters would benefit from a cheaper currency and banks would benefit from the combination of stronger economic growth and higher long-term inflation expectations (which would pave the way for a steeper yield curve). Inflation is the silver bullet that the Germans need to solve their imbalances, but they have completely ignored it. Needless to say, the market is also not pricing this in. But in two years, it would be a mantra in Germany. This is a thesis we have been pursuing since the early part of the year, and apparently it is now becoming mainstream. Here is the FT last week:

“Eight years of austerity and a prolonged fall in central bank borrowing rates and bond yields have failed to deliver sustained economic growth. Hence the rise of populist politics, while calls for fiscal stimulus are steadily growing. It is a path being taken by Canada, with a post-Brexit UK looking to loosen the shackles. Both US presidential candidates, notably Donald Trump, are also focusing on the fiscal side of the stimulus equation. Meanwhile, the test bed over the past two decades for policy experiments has been Japan and there, talk of “helicopter money”’ — whereby the budget deficit is financed by a permanent increase in the central bank’s monetary base and not via government bonds — is the current hot topic of debate.”

“Any concerted fiscal stimulus in developed economies has the potential to change investors’ mindsets. For the broader global economy, any significant fiscal stimulus through infrastructure spending, vouchers for consumers and/or some combination of tax cuts is seen boosting growth and pushing up inflation expectations. Given the extreme hunt for yield in recent years, the prospect of major fiscal expansion, particularly if undertaken by leading economies in unison, would amount to a significant shock for plenty of portfolios. A decisive flick of the fiscal switch to loosen austerity would herald a stampede from the best performing sectors of global markets. As yields and volatility rise, investors embark on a rotation into cyclicals.”

The transition process will be bumpy and volatile:

For us, the 35-year bond bull market will soon start to transition towards a peak. However, just because a bull market ends does not mean that a bear market is immediately around the corner. Often markets have to go through a “bottoming” process before a new secular trend is established. We are in such a transition phase now, which means that while the path of least resistance for yields is upwards; while a sustained spike in yields is not yet in the cards, the peak of the 35-year old bond bull market starts to form. It may however take another two years before we can form a definite judgment that the bond market has indeed passed it peak.

|

Main drivers:

|

Commodities and Economic Highlights

Commentary by Robert Balan, Chief Market Strategist

The US Dollar should remain benign for hard assets; a rally in oil prices in H2 2016 should weaken it further

With the Fed unable to change monetary policy setting much, and the risk remaining to the upside, the US dollar will tend to trade according to factors other than those related to interest rate differentials and monetary policy divergences. Nonetheless, the market’s perception of what the Fed will eventually do with respect to policy tightening will be a significant factor in the very short term. This factor is especially significant at present due to the FOMC meeting scheduled this week, although we have great confidence in the outcome of the forthcoming FOMC meeting – which is nothing.

However, this is not to say that the meeting this week is unimportant; in fact the US Dollar has been trending higher in the past several weeks due to expectations of a change in the FOMC statement this time around. Nearly every piece of economic data since late-June have been better than expected. This includes the non-manufacturing ISM, job creation, retail sales, industrial and manufacturing output, and existing home sales. Headline and core CPI were also firmer than anticipated. Therefore, the FOMC statement will not close the door on a September move. It will reaffirm that as the Fed's objectives are approached, gradually removing accommodation is appropriate. The basis for a more hawkish stance can be had from continued improvement in the US labor market, favorable consumption patterns, and a stable international environment. But September is too close to the election, so we believe that the Fed is unlikely to tighten policy until December – if conditions still warrant the move by then.

Outlook of a policy tightening by year-end is unlikely to push the US Dollar much higher than where it is right now. Under those conditions, other factors could tip over the balance either way. One such factor is a sharp rise in oil prices which we expect during the later part of H2 2016. We submit the proposition that a forthcoming sharp rise in oil prices could lead to, or help, in weakening the US Dollar going into the late part of H2 2016 and even further. A sharp rise in crude oil prices, and attendant weakening of the US Dollar, should help spark renewed interest on the Commodities asset class, as well as provide underlying upside pressure on inflation and inflation expectations. The recent sharp rise in oil prices will be factored-in in inflation measures by late Q3 2016. Development in inflation prospects along those lines will loop back, and should further provide boost to commodity prices and add to the downward pressure on the US Dollar.

There is significant amount of academic work which investigated the long-run relationship between US Dollar rates and the price of oil. The academic work generally finds that US Dollar exchange rates and the price of oil are cointegrated and exhibit a positive long-run equilibrium relationship: that is, higher oil prices are associated with the decline of the US Dollar, and lower oil prices can be associated with the rise in the value of the US currency. Furthermore, the literature generally finds that oil prices Granger-cause exchange rates, but not vice-versa, meaning that causality flows from oil price to the USD exchange rate. That kind of relationship is not difficult to show with normal regression analysis. Indeed, the causality goes from oil prices to the USD exchange rate.

Fortnightly charts:Capital expenditures in the oil and gas sector; When savings rise, but investments falls the excess savings make rates fall; Fiscal spending is essential when monetary policy reached its effective limits

|

|

|

|

|

|